1910 Broke Reality: The Modern World’s Greatest Mental Meltdown

Hello everyone. Let’s strap in – or don’t, because apparently in 1910 they barely bothered with safety, restraint, or anything resembling moderation. What we have here is an ode to The Vertigo Years that could be mistaken for a giddy love letter to the era when humanity discovered the miracle of moving faster than horseback and immediately decided civilization was over. Buckle up – not for speed, but for an overindulgent nostalgia trip where typewriters are traumatic, bicycles are lust-inducing, and Freud lurks in the wings like some psychoanalytical ninja waiting to diagnose your existential dread.

Speeding Into Madness (and Trousers)

The book’s most gleeful obsession is how people in 1910 thought everything was moving “too fast.” Apparently, the bicycle craze alone was a moral apocalypse. Women – existing in public, on two wheels, sans corsets – were treated like NPCs that just discovered the sprint button in a Victorian morality sim. Moralists feared it meant sexual deviancy. Doctors warned about the bicycle’s catastrophic effects on the youth, as if a comfortable seat and chain drive threatened to unravel the social fabric. Let’s not forget pseudo-scientific height calculations implying cyclists were essentially 40-foot titans – a steampunk kaiju fantasy I now cannot unsee.

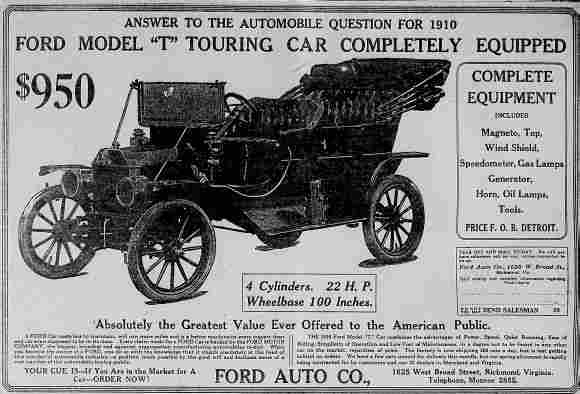

And just when you think it’s parody, we get the prophetic warning: speed turns us into machines. That’s right – your great-grandparents saw the Model T the way conspiracy YouTube sees AI-powered toasters. Honestly, if gaming forums reacted to balance patches the way Parisians reacted to modern transport, we’d have duels at dawn over nerfed drop rates.

American Nervousness – The Original Patch Notes for Anxiety

The second act in this turn-of-the-century drama is “American Nervousness” – or, for people who like their diseases city-branded, “Newyorkitis.” This was no satire; it was a genuine diagnosis for white-collar collapse brought on by a blend of rapid tech change, mechanical noise, and the horror of increased workflow efficiency (a fate worse than leeches, apparently). The data is actually fascinating: mental hospital patients in Germany tripled between 1870 and 1910, and nervous system cases rose sharply. But the framing is drenched in that romantic “we were too fragile for modernity” handwringing that makes me want to check the ping on humanity’s resilience servers.

From a medical perspective – yes, let’s put on the lab coat – neurasthenia reads like the common cold of the upper classes: half lifestyle complaint, half legitimate burnout. In gaming terms, it’s when you grind office XP so relentlessly that your mental stamina meter hits zero, but instead of “resting,” you’re sent to a spa for a month to recover from the trauma of filing paperwork too quickly.

Modernism: The Rage Quit of Traditional Art

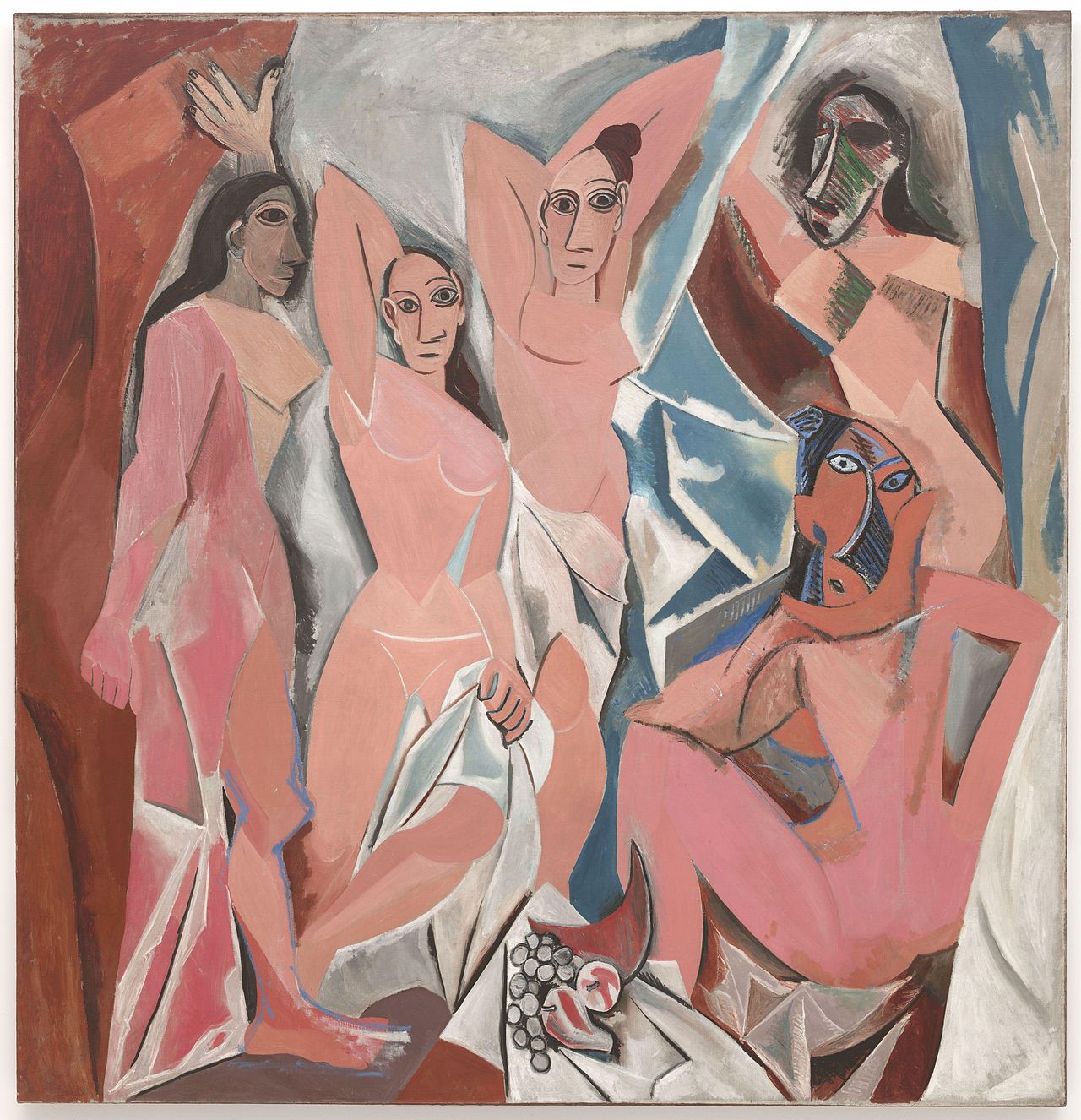

Then there’s the art chapter, which is equal parts glorious and ridiculous. Stravinsky, Kandinsky, Picasso – history’s equivalent of modders breaking all the rules and pushing a patch nobody asked for. The *Rite of Spring* premiere descended into an audience PvP brawl. Objects were thrown. Fists were used. People rage-quit the theatre in real time. Funky time signatures: apparently the Devil’s DLC.

Photography’s rise is rightly noted as a catalyst for abstraction – when everyone can snapshot reality with a Kodak, painters basically uninstall the realism engine and boot up an abstract shaders mod. Kandinsky’s mystical synesthesia paintings and Picasso’s primitivist blocky nightmares were less about beauty, more about yeeting the old rules out the window just to see what stuck. Predictably, critics claimed such work “breathed the poison breath of vice” – classic 1-star Amazon review energy.

Freud vs. Weber: Fight Night in the Cerebral Arena

Finally, we get the intellectual boss battle: Weber vs. Freud. Weber runs the “Protestant Work Ethic” build, claiming capitalism evolved naturally from religious discipline. Freud, meanwhile, queues up with a “Your Psyche is Screwed” deck, arguing capitalism dissolves human nature into a soup of repressed animal urges. Both are partially right and therefore infuriating. Weber’s capitalism-as-faith feels like a rogue religion mod, while Freud’s sublimation concept is pure alchemy – taking primal desire and crafting a socially acceptable enchantment on it, like turning +10 Lust into +5 Overtime Productivity.

The book (and this review article) coyly refuses to pick a side, but the underlying theme is painfully relevant: are our shiny, earth-shattering inventions an expression of what makes us human, or the countdown clock to our own mental firmware failure? In other words: should we hit “update now” or “remind me tomorrow” on civilization itself?

Final Diagnosis

This piece is well-researched, drenched in delight for the period, and offers seriously interesting historical parallels. Yet it’s wrapped in that whimsical-eye-roll style of nostalgia that treats the early 20th century like a sepia-toned cautionary fable. The problem: beneath the charm lies a tendency to romanticize fragility – as if humanity is forever one technological patch away from collectively lying down in a sanatorium until it all passes.

Still, as a bridge between past and present anxieties, this delivers. You’ll leave with a colorful mental gallery of 1910’s bizarre blend of progress hysteria, art rebellion, and intellectual sparring – and maybe a reminder that every generation thinks it’s teetering on the brink. Odds are, much like in 1910, we’ll keep barreling ahead anyway, occasionally stopping to accuse the bicycle of corrupting our moral fiber.

Verdict: A net positive read, but handle with care – too much at once and you might end up with a nasty case of Neo-Neurasthenia.

And that, ladies and gentlemen, is entirely my opinion.

Article Source: 1910: The year the modern world lost its mind, https://www.derekthompson.org/p/1910-the-year-the-modern-world-lost